Cooking Up a Solution to Poverty

Wellesley College Student's 'Solar Cooker' is Designed to Reduce Pollution and Disease

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE:

June 27, 2008 |

|

|

Wellesley College senior Catlin Powers (center)

with her host family in Awuju village, Tibet.

|

WELLESLEY,

Mass. -- In many places in Tibet, villagers spend much of their day in the cold, collecting wood and dung for cooking and heating, often on dangerous mountain slopes. The time spent collecting fuel especially limits women’s ability to become educated or engage in other economic activities. The risks involved and pollution formed by fuel combustion also affects their health and productivity.

During a visit to the region, Wellesley College senior Catlin Powers’ interest in the health, comfort and social status of women motivated her curiosity about designing a product to allow these women to cook with solar power.

“Women worked hard to collect enough dung and wood for fuel,” she said. “Barehanded dung collection by mothers presented a health concern for families and especially for young children. Since dung and wood fuels emit high levels of small particulates and carbon monoxide, they present a significant health threat from indoor air pollution while their green house gas emissions contributed to climate change.”

Powers, the daughter of Charles Henry and Joan Takahashi Powers of Los Gatos, Calif., has worked in collaboration with MIT students and villagers from Amdo, Tibet, to develop an innovative solar design for cooking and heating that works to address villagers’ concerns.

|

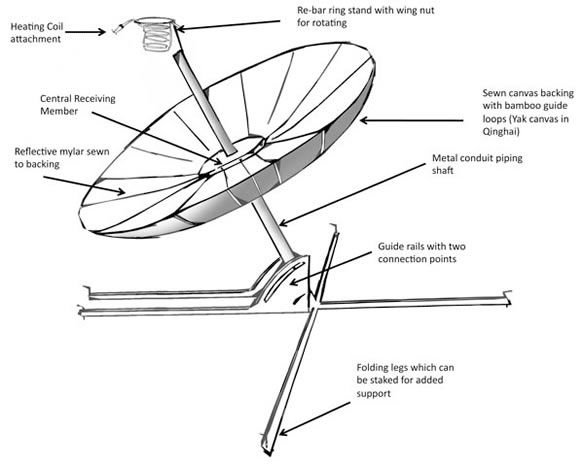

Diagram of the SolSource SolSolution, a 2-in-1 solar cooking and heating device. To learn more, click here. |

At Wellesley, Powers started by organizing a non-credit Tibetan language course. The course drew the interest of students at other Boston- area colleges and universities and, through them, she began to learn more about Tibet. Powers, a chemistry and environmental studies major, and MIT student Scot Frank began to discuss the interactions between environmental issues in high altitude regions and modern technologies.

Some nomads in Tibet used small government-issued solar panels to harness the sun and provide light, but these units were not capable of heating or cooking. Other families owned solar cookers and liked them because they reduced the need for time intensive fuel collection and also decreased indoor air pollution. Yet the cookers were made of concrete and so heavy it took four people to lift them.

“Among other design flaws, they were too heavy to take to the fields during summer and thus only one meal could be prepared using sun energy,” Powers said. “Villagers stated that increased portability and the addition of a heating functionality were the keys to improving fuel-related problems faced by villagers and nomads alike.”

While in Tibet, Powers and Frank teamed up with students at Qinghai Normal University to decide which design drafts for a solar cooker were the most appropriate from the perspective of their villages, as well as what materials were locally available and cost effective. They also began to develop monitoring and training programs for the project. Upon returning to Boston, they worked with MIT students Brad Simpson and Orian Welling to further develop and construct a prototype.

|

Powers collects yak dung for emissions testing. |

The project, called SolSource Tibet, incorporated locally available materials from Qinghai and used the villagers’ traditional knowledge. Made of bamboo rods, a yak wool canvas and a sewn mylar reflector, the cooker can be dismantled as quickly as a hiking tent and transported easily.

This summer, the team is building an online fuel database, finishing the translation of training materials into colloquial Tibetan and testing and altering the cooker before introducing it to villagers. In January 2009, the students will deliver models of the solar cooker to village leaders and receive their feedback.

The team has partnered with solar cooker factories in western China to produce the new design and are considering training programs in more remote areas to teach people to construct the SolSource cooker themselves. They have worked to build connections with nongovernmental organizations and individuals across the Himalayan region and plan to share their innovations with them to disseminate the product further.

The solar cooker is just the start for students involved in the project, who want to continue to work toward sustainable rural energy options for high altitude regions. They have partnered with Wellesley College Professor Daniel Brabander and Professor Kristen Jellison of Lehigh University to analyze village water samples, aiming to find solutions for villagers whose water is contaminated by bacteria and heavy metals. They are also planning future projects related to composting for fertilizers, additional simple energy generation solutions, water filtration and science education.

“We don’t want to end our involvement in the region with the conclusion of this project,” Powers said.

For more information on SolSource Tibet and ongoing projects, visit www.oneearthdesigns.org/projects/solsource.

Since

1875, Wellesley College has been a leader in providing an excellent

liberal arts education for women who will make a difference in the

world. Its 500-acre campus near Boston is home to 2,300 undergraduate

students from all 50 states and 68 countries.

### |