Patriotism, Power, &

Privacy Online

Accelerating Digital Opportunities for All Peoples:

Our Collective Response in the Light of Global Info Poverty

Held on Tuesday, April 2, 2002 at 4:30 pm in PNW 239

Held on Tuesday, April 2, 2002 at 4:30 pm in PNW 239

Anthony Wilhelm, Director of the Digital Divide Network, Washington, D.C.; author of Democracy in the Digital Age

Although digital information and communications technologies are consolidating in the hands of a few media conglomerates-bent on serving up primarily a range of entertainment programming-the media climate is far from bleak. Young people have the potential to shape the emerging media landscape for social good-as consumers, investors and, most important, as producers and innovators.

Unlike the diffusion of prior communications tools, new media is largely being driven by the use patterns of teenagers and young adults in whose hands portend the shaping of what remains a nascent social practice. With experiments such as the Mellon Residential Life Grant, Wellesley can contribute significantly to the debate over effective ways to implement and take to scale mediated communications environments that break down traditional barriers and borders-educational, socioeconomic, geographic and otherwise.

This lecture will focus on young adults as producers and shapers of an emerging media environment that can re-engage them in local civic practice as well as develop a broader global identity.

Full Transcript

After reading the interim report and update on the interim report that Wini Wood sent to the Mellon Foundation on progress you all have made in your Residential Life Project, I was eager to accept Wini's gracious invitation and spend time hearing more from you about the impressive and important work underway here at Wellesley. It is indeed an honor and privilege to offer reflections on an issue that has been near and dear to my heart for many years, initially as a researcher and scholar (having conducted early studies on computer and Internet access and use among Hispanics and other communities of color) and of late, in my capacity at the Benton Foundation, engaging the fields of philanthropy, business and government in articulating the benefits information and communications technologies can deliver to strengthen communities and create economic and educational opportunity, all for the purpose of increasing public-private investments in this arena.

It is practically impossible to imagine a future that is not saturated with information and communications technologies. The Internet-the upstart of the 1990s-is rapidly fading into the background noise of our daily experience, particularly for a younger generation, which Neil Howe and William Strauss refer to as The Millennials, those born since 1982, making the oldest of them about your age.

According to the authors of Millennials Rising, this cohort is distinct from the preceding generation, "Gen. X": Millenials are more numerous, more affluent, better educated and more ethnically diverse. Based on surveys, they describe themselves as not lost but found, born into an era when Americans are expressing more positive attitudes about children and young adults. They are also optimistic, upbeat about the world in which they are growing up. They are not self-absorbed but cooperative team players. Importantly for the purposes of my remarks, you all believe in the future and see yourselves on the cutting edge of progress, particularly when it comes to your fascination for and mastery of new technologies [1].

As relates to our theme today, Millennials use many types of technology, often instant messaging friends, doing homework, talking on the phone, and listening to music, all at the same time. Many of you have your own websites and are much more adept users of technology than your parents, many of whom still rely on snail mail to keep in touch.

On a typical day, Millennials will spend an average of 6.5 hours using media-watching television, listening to music, reading and working on the computer [2]. What we know, as Marshall McLuhan suggested two generations ago, is that (young) people in general use new media to supplement, not supplant, older forms of media. Those who spend a lot of time with computers also watch more TV and read more than most others [3].

Young adults occupy a rich media environment, and the computer is quickly occupying more time in this digital landscape. Email, IM and chat groups are incredibly popular among teens-as are downloading music files and increasingly buying products online [4]. Among 18 and 19-year-olds, 91% use email and 83% use instant messaging, with over half (56%) of older teens saying they prefer the Internet to the telephone [5]. With the advent of high-speed broadband, always-on Internet services and next-generation wireless tools, these numbers-and the time youth spend online (increasingly through mobile technologies) will in all likelihood increase [6]. With early market development of virtual or immersive environments, with experiences potentially indistinguishable from reality, who knows what the future holds [7]?

The potential of the Internet-and the subject of this talk-is to explore how emerging communications tools can address important social issues, such as community building and economic advancement.

The Benton Foundation's mission is to demonstrate the potential of communications technologies for solving social problems, particularly problems afflicting those communities on the margins of economic, educational and civic life. The view of our founder, William Benton-an advertising pioneer of the 1930s, later the head of Encyclopedia Britannica and United States Senator from Connecticut-was that technology, if used effectively, can be an enabler, a tool to empower communities and institutions in addressing important needs. The prevalent medium of Mr. Benton's day, radio, according to our founder, should be used for more than just selling commercial products: It should serve higher social goals. As Mr. Benton expressed in 1936, "if the great universities do not develop radio broadcasting in the cause of education, it will, perhaps, be permanently left in the hands of the manufacturers of face powder, coffee and soap, with occasional interruptions by the politicians" [8].

What Mr. Benton did in the late 1930s, as vice president of the University of Chicago, is not unlike what students and faculty are undertaking here at Wellesley: he tried to weave leading-edge communications technologies-again, in his case, radio and motion pictures-into the fabric of the university's intellectual and social life.

What he believed was that radio and television as broadcast media, are a public trust or resource, not unlike the public parks, and should be husbanded with attention to serving society's needs. For example, one of the great ideas of the 1930s was to create "The University of the Air", a vast system of educational offerings served up over what was then called the ether or airwaves-a virtual schoolhouse forecasted to make textbooks and classrooms obsolete. Sound familiar?

If we fast-forward 70 years to today, the same issue is before us relative to the new digital media: will they be used predominantly to entertain and amuse or can they be harnessed to serve society's critical needs? How many of you have seen the Intel ads where the sepia-toned aliens learn to use the Pentium-4 processor to play more lifelike video games and to download multimedia entertainment? Corporations are selling broadband as a way to deliver video-on-demand and interactive video games.

Just to zero in for a minute on the video game industry: The video game craze is astonishing and seems to have no end in sight. In 2000 sales of hardware and software for interactive games, eclipsed Hollywood for the first time, with sales totaling $8.2 billion versus just $7.75 billion in U.S. movie box-office receipts [9]. There are thousands of titles-many of which are purveying violence and misogyny; yet despite the enormity of the market-and the relatively high penetration in underserved communities-nobody is creating marketable educational content let alone applications for community building or civic engagement (with rare exception).

With the emerging digital television, virtual reality and broadband cyber environment, developers are hoping to generate demand for new technologies and applications by supplying content centered on sports, pornography, gambling and other forms of diversion. While it may indeed be exciting to be in the huddle with the quarterback as he calls a play in the next Superbowl, wouldn't it also be exciting to tag along with Sacagawea as she guides the Corps of Discovery westward through tribal lands or to assist Marie Curie as she sets up her laboratory in a small, glass-walled shed in 1898 Paris, only four years later to confirm the existence of the 88th element, radium?

Entertainment applications may be what drive the market but can we cordon off a fraction of space and attention for intellectual purposes? Can we elicit a socially beneficial dimension to these tools that can uplift communities, especially those on society's margins? Can't we harness some of this potential-and steer the eyeballs of millions of young people-to address their educational and social needs? What difference can you make in improving the media environment in which we are all immersed, whether we like it or not?

II

The Wellesley community can already bear witness to the fact that digital media-e.g., e-mail, IM, and online conferencing-can, if used appropriately, be a force that breaks down borders, walls and barriers.

At a conference I attended in March in Berlin on 21st-Century Literacy, world leaders such as German Chancellor, Gerhard Schroder, and Madeline Albright, former Secretary of State under Bill Clinton, spoke of the power and promise of information and communications technologies to knock down walls, very appropriate given this city's recent history.

Chancellor Schroder asserted boldly that digital literacy should now take its place as a basic literacy alongside reading, writing and arithmetic [10]. Indeed, in its bid to become the most competitive knowledge-based society by 2010, the European Community generally embraces the pivotal role of information and communications technologies in underwriting lifelong learning and economic productivity, particularly given its aging population [11].

What remains a challenge, from reading the reports on the Mellon Residential Life Project, is this whole notion of building 21st-Century Literacy skills-not just using the media effectively in your academic pursuits (e.g., doing online research) but also in cultivating the mores appropriate for online interaction and community building. These challenges notwithstanding (and clearly they are enormous) your experimentation remains a bellwether as a leading-edge demonstration project, providing vital empirical data and experience to assist in shaping what's to come in e-community building.

Interestingly the 21st-Century Literacy Conference was hosted under the shadow of the Brandenberg Gate-the symbol of a city at the center of former political strife. It is currently shrouded under a drop cloth, undergoing restoration and renewal. Since German Telecom, the AT&T of Germany, is supporting the renovation project, the company has taken the opportunity to use the Gate as a giant advertisement for their Internet service, called T-Online. The slogan brandished across the famous landmark declares that: Im Internet ist alles moglich.

Clearly widespread euphoria over the future of society immersed in technology continues to exist even after the dot-com bubble burst and in the post-9/11 environment. Millenials lead the charge. And the potential is enormous, as I will discuss shortly. Yet this excitement continues to mask the forms of social and economic exclusion that exist in the United States and between developed and developing nations. The Wellesley experiment is fortunate-everyone has access to these tools, I assume in your rooms and dorms-and according the interim report, every demographic seems to be participating equally.

This is not true for society as a whole.

While we talk about Internet benefits, approximately 80% of the world's population has yet to make a phone call-a difficult proposition for the1.2 billion people who still live on $1 or less per day. Yet we know to tear down the walls of economic exclusion, we need to create markets to raise standards of living in communities outside the boundaries of global trade lest poverty continue to sew the seeds of animosity and envy between haves and have-nots [12].

In our own backyard social exclusion and alienation persists, whether it be in south Boston or the tribal lands of the Western United States where communities continue to persist without basic information and communications infrastructure. High dropout rates and lack of preparedness for employment in today's economy deepens social exclusion. At the end of 2001, only about 1 in 4 low-income households was connected to the Internet compared with 8 in 10 households earning over $75,000 per year [13]. Many youth-particularly youth of color-attend public schools that continue to be educated with very little access to and effective integration of emerging technologies [14], a missed opportunity given what we know about the positive impact of virtual learning environments in improving motivation and performance of at-risk teenagers [15]. Even colleges, such as tribal colleges, historically Black colleges and the like could only dream of doing what has been accomplished here at Wellesley.

So as the science fiction writer, William Gibson suggests, the future is here; it's just not equally distributed. Without access to these tools, as well as the ability to use them effectively, we are missing a necessary link in building communities and re-connecting folks on the margins of society.

III

As I mentioned, Millennials see themselves on the cutting edge of something new. This society and culture in which communications tools are pervasive is second nature for many young adults. Indeed, they themselves are actors and co-creators in its unfolding-both as consumers and as producers of new content and applications. Although digital information and communications technologies are consolidating in the hands of a few media conglomerates [16], the media landscape is far from bleak [17].

As consumers, youth and young adults are increasingly targets of corporations, with 32 million teens accounting for $172 billion in spending money in 2001, half of whom are now shopping online [18]. ABC Network's recent attempt to roundhouse Nightline and replace it with David Letterman's Late Show in order to attract advertisers salivating over the young adult niche market underscores this reality.

As consumers, youth have significant economic and political power-e.g., in promoting green products, in supporting fair labor practice across the globe, and so forth. In the 1980s, institutions used their clout to pressure social and political change-for example, through divesting of financial holdings in South Africa. Yet today individuals are exercising their power as consumers (as critical market segments or niches) and investors (e.g., through socially responsible investments) to influence market behavior. A recent Marymount University poll of 1000 adults revealed that 75% of consumers would avoid shopping at stores that sell sweatshop-made clothes [19]. But of course we need to know who the worst perpetrators are and we must organize and engage to act on this information. Undoubtedly the role of the Internet and other digital technologies here is pivotal.

Most important, youth are not just consumers but also producers, riding the crest of the wave of new innovation and practice that has blossomed since the mid to late 1990s [20]. Because in your hands these tools are second nature, you have the potential to shape the emerging media landscape for social good.

The wonderful power of the Internet and other digital media is their interactivity, the ability of users to be producers and not just passive recipients-as was the reality with one-way, broadcast media [21]. The Internet is also an efficient and effective organizing tool, enabling communities of interest across the globe to broaden the scope of involvement and engagement in their issue at relatively low transaction costs. Finally, to be an Internet publisher, start-up costs are substantially lower than those of traditional, saturated media-that is, broadcast media-allowing young people in basements or community centers to easily hurdle entry barriers, becoming global denizens [22].

The young entrepreneur, Omar Wasow, who directly upon graduating from Stanford University founded New York Online, a cyber-community of New Yorkers from all walks of life, is now the architect of BlackPlanet (www.blackplanet.com), a web portal that brings the worldwide African diaspora together into an online community that allows members to cultivate personal and professional relationships, gain access to relevant goods and services and stay informed about the world.

Unlike the diffusion of prior communications tools, new media are being driven partly by the use patterns of teenagers and young adults in whose hands portend the shaping of what remains a nascent social practice. With the rollout of print in the Fifteenth Century or the telegraph in the Nineteenth Century, the role of young people was peripheral at best. With the commercial Internet only 1500 days old, clearly there is a primary role for you to shape and lead as this medium matures.

As I have mentioned, surveys show that Millennials are team-oriented and are engaged in community service, volunteering and becoming involved, for example, with efforts to improve the environment, reflecting a keen interest in the unfolding global civil society.

Breaking down the barriers to the development of global identities and perspectives is of critical importance moving forward. What is heartening is to think about what students are doing well after classes have ended, you've eaten your lovely dining hall meals, perhaps watched a little television, done some homework-and then in this time period between 10 pm and the wee hours of the morning, this prolific online activity is underway. My challenge to you is to seize the opportunity to reach out and extend your own sense of global identity and sense of responsibility as you invent community building for the twenty-first century.

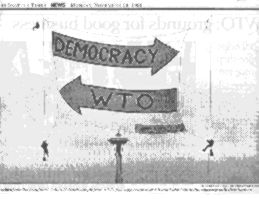

No recent event better highlights this commitment than the World Trade Organization process, in particular the meetings in Seattle in 1999. At this event, ministers and industrialists convened to discuss the best arrangements to buttress world free trade while, unbeknownst to them, student, labor and nonprofit groups were using the power of the Internet to organize to counteract this trend. A photo taken by a Seattle Times reporter best captured the tension, showing arrows pointing in one direction for the WTO decision making process and in the opposite direction for democracy, democratic self-determination in the minds of the protesters having been undermined by the opacity of the transnational decision making format.

Figure 1: Contesting Values: Democracy and Commerce

One of the consequences of September 11 has been a worldwide rise in racism, xenophobia and violence against immigrants, particularly those of Arabic descent [23]. In the U.S. and Europe, anti-immigrant platforms and parties continue to gain ground and state-sponsored violence has expanded in the name of quashing disempowered groups branded as terrorists.

To mitigate the effects of these parties of intolerance-and to begin to hurdle the barriers that separate religious, ethnic, racial and cultural groups in or society-I believe strongly that you can harness the power of the Internet in cultivating a more tolerant and inclusive civil society. Government, philanthropy, business and, yes, the university community, among others, should be in the forefront of experimenting with communications technology in the post-Sept. 11 environment to promote understanding between and rapprochement of cultures-while at the same time, through this example, encouraging free and flourishing civil societies, both in our country and, say, in the Mediterranean Basin, where much of the new radicalism is incubated.

Opening up to the wider world-not just through students abroad but more seamless offerings such as ongoing electronic conferencing and trans-university curriculum development-would favor mutual knowledge and understanding [24]. One idea might be to reach out to a university, perhaps in the Mediterranean Basin, to cultivate an interest in using the new media to explore mutual understanding, both culturally and in ascertaining the impact of the technology on civil relations. The potential for cross-cultural dialogue and cooperation could be stimulating.

The surge of different forms of radicalism and intolerance reveals the deficit of dialogue and understanding between cultures-not to mention symptoms of growing economic inequalities between rich and poor-and academic exchange, complemented and extended with communications technologies, such as email and conferencing, may just transform attitudes by allowing younger generations to compare their respective national values and cultures-while deepening this nascent internationalism already percolating among Millenials.

IV

Clearly Wellesley is well connected, using email and virtual environments to resolve problems. Have these tools led to greater tolerance among groups? Has it allowed for collective action on a scale and speed less effectively undertaken in face-to-face setting?

Cyperspace represents another place in which people can communicate socially and politically. Through these new venues people can engage in many sorts of activities: join interest groups, vote in elections or engage in decision-making activities. These really constitute new "sounding boards" where in your case the members of the university community can raise concerns online and express ways to address these problems. Wellesley of course is an experiment of sorts in exploring the extent to which these forums can be effective in setting agendas, making decisions, negotiating differences and arriving at hard-fought compromises.

A favorable answer to the preceding questions depends in part on the degree to which conversations and dialogue in cyberspace allow for critical-rational reflection and deliberation. There are 3 essential attributes that make deliberation possible: First, political messages of substance can be exchanged at length; second, there is opportunity to reflect on these messages; and finally, these messages can be processed interactively, with opinions being tested against rival arguments [25]. On the face of it, email chat rooms and discussion groups seem ideally suited to deliberative exchange, since the asynchronous and virtual nature of the technology allow for reflection, while the software architecture enables participants to respond to postings and to incorporate their remarks effortlessly into an ongoing thread.

Is the Internet then the elixir to cure the ills that over the past several decades have afflicted our democracy? Can be harnessed to cultivate a global civil society?

In my research, I pose 4 primary questions that you might want to contemplate as you evaluate and assess your own ongoing experiment looking at the impact of technology on residential living here on campus. These questions are exploratory and are lenses through which we might "deconstruct" elements of online discussion in order to analyze and to generalize about the nature and scope of online conversation [26].

The first issues centers on providing information versus information seeking. In my research, particularly when it comes to political chat, participants are more than eager to chime in and express their point of view and substantially less likely to make requests to fill gaps or seek exploration of alternative views on issues about which they are interested. While self-expression is clearly important, we also need to "listen" to others, to enter dialogue in order to broach understanding and act collectively in the light of day [27].

Second, there is a tendency with technology-and the straw polls and plebiscite-like activity that is rampant on commercial portals-to want to register individual preferences, and then aggregate them, rather than encouraging exchange and thoughtful response to extant discussion threads, so we are less aggregating preferences and more looking for common ground and points of contention that might require further discussion, debate and elaboration. While some scholars have heralded the idea of cyberspace as a "gathering place" - provoking new arenas of belonging-the social model seems an attenuated one at best, particularly if we are looking at addressing social and political problems. People need to feel responsible before other community members so that citizens and community members are more than the fraction of a passive, consumer public. For example, in the Mellon interim report, the discussion of issues and comments "falling between the cracks" was interesting, since often with multiple discussions occurring simultaneously, it is possible and perhaps quite likely, without some artfulness, that some requests will go unrequited.

Third, through chat groups and online discussion forums, participants tend to gravitate toward likeminded individuals so that cyberspace largely becomes an extension of the social networks and hobby groups one would join and belong to in your physical community [28]. What does this homogeneity imply for overcoming difference, encouraging tolerance and understanding, as well as broadening our horizons, particularly given the global possibilities of these technologies?

Finally, the last issue I examined gets to the heart of the critical-rational dimension of online discussion. In short, we need to be able to validate the truth of claims by supplying reasons for support in the public sphere; otherwise, claims cannot be arbitrated. Here we do see some encouraging results, where the time and distance allow for reflection and considered judgment, which might not be possible in a face-to-face format.

Of course the architecture of a network or online discussion-including its functionality and presence of expert moderation-will affect the quality of online exchange, and I'm encouraged you are contemplated using new software, as discussed in your conversations with Benjamin Barber, to increase the quality of online discussion.

I have covered a lot of territory in these remarks. They are meant to spark your own curiosity and excitement in continuing to explore and examine a truly new and potentially empowering mode of communications. Clearly there are many technological hurdles-and technology continues to change so rapidly that it is sometimes hard to keep pace with the latest device or tool. But remember these are only tools.

The great challenge on the horizon in the 21st-Century is a social, not a technological one-that is to say, coming to terms with our diversity. Encouraging a diversity of viewpoints and cultures ought to be the hallmark of a liberal university, and the technological innovations hopefully will bring us closer to an inclusive global civil society that honors diversity as its lynchpin.

Endnotes

- Howe, Neil and Strauss, Strauss. Millennials Rising: The Next Great Generation. New York: Vintage, 2000. 6-10.

- Roberts, Donald F. and others. Kids & Media @ the New Millennium. Menlo Park: The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. 1999. 18.

- McLuhan, Marshall. Understanding Media: The Extension of Man. New York: McGraw-Hill. 1964. ix.

- Lenhart, Amanda, Rainie, Lee, and Lewis, Oliver. Teenage Life Online: The Rise of the Instant-message Generation and the Internet's Impact on Friendships and Family Relationships. Washington, D.C.: Pew Internet & American Life Project. 2000. 6.

- Pastore, Michael. "Demographics: Internet Key to Communication Among Youth". Online. http://cyberatlas.internet.com/big_picture/demographics/article/0,,5901_961881,00.html.

- Pastore, Michael. "Broadband Users Pull Ahead in Online Hours".

- Kaplan, Karen. "A Virtual World Is Taking Shape in Research Labs". Los Angeles Times. February 5, 2001. Online. http://imsc.usc.edu/about/IMSC_LATimes_Web_2_5_01.pdf.

- Hyman, Sidney. The Lives of William Benton. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. 1969. 176-7.

- Kharif, Olga. "Let the Games Begin-Online". BusinessWeek. December 13, 2001. Online. http://www.businessweek.com/technology/content/dec2001/tc20011213_2329.htm.

- Schroder, Gerhard. Keynote speech on 21st Century Literacy. Berlin, Germany. March 7, 2002.

- Secretariat General of the Commission of the European Community. "Presidency Conclusions". Barcelona European Council. March 15-16, 2002. Online. http://www.europa.eu.int/comm/barcelona_council/index_en.html.

- Cohen, Nevin. "Rural Connectivity: Grameen Telecom's Village Phones". San Francisco: World Resource Institute. 2001.

- U.S. Department of Commerce. A Nation Online: How Americans are Expanding Their Use of the Internet. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Commerce. 2002. 11.

- U.S. Department of Education. "Internet Access in U.S. Public Schools and Classrooms: 1994-2000". Washington, D.C.: National Center for Education Statistics. 2001.

- The Benton Foundation. Toward Digital Inclusion for Underserved Youth. Washington, D.C.: The Benton Foundation. 2002. 33-40.

- For an excellent discussion of what's at stake with the consolidation of digital media, see the Media Access Project's website at http://www.mediaaccess.org/programs/diversity/index.html.

- Rather than underscore the pessimistic side of media concentration as reinforcing antidemocratic tendencies in current climate, this paper highlights the new possibilities inherent in innovative communicative practice and thus follows David Zaret's very sensible corrective to the glass-half empty approach of critical theory and postmodernism. See Zaret, David. Origins of Democratic Culture: Printing, Petititions, and the Public Sphere in Early-modern England. Princeton, Princeton University Press. 2000. 275ff.

- Wood, Michael. "Teens Spent $172 Billion in 2001". Teenage Research Unlimited. January 25, 2002. Online. http://www.teenresearch.com/PRview.cfm?edit_id=116.

- International Communications Research. "The Consumer and Sweatshops". Marymount University. November 1999. Online. http://www.marymount.edu/news/garmentstudy/.

- Wireless carriers are targeting young adults between 16 and 24 as the growth market of the future, with wireless service buyers in this age group likely to jump from 11 million today to 30 million in 2004. Youth want both a personalized, wireless phone experience as well as the latest and greatest in technology, according to wireless carrier marketers.

- Neuman, W. Russell. The Future of the Mass Audience. New York: Cambridge University Press. 1991. Introduction.

- Adler, Richard P. Changing Rules in the Market for Attention: New Strategies for Minority Programming. Washington, D.C.: The Aspen Institute. 2000. 7.

- Finn, Peter. "A Turn from Tolerance". The Washington Post March 29, 2002. Online. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/articles/A33967-2002Mar28.html.

- The European Commission recently extended its trans-European co-operation scheme for higher education through Tempus III, a Union effort to favor mutual knowledge and understanding between the European Union and the Mediterranean, through education and culture exchanges and dialogue. See .

- James Fishkin, "Beyond Teledemocracy: 'America on the Line'", The Responsive Community 2(3): 16.

- Wilhelm, Anthony G. Democracy in the Digital Age: Challenges to Political Life in Cyberspace. New York: Routledge. 2000. Chapter 5.

- Barber, Benjamin R. Jihad vs. McWorld. New York: Random House. 1995. 276ff.

- Huckfeldt, Robert R. and Sprague, John. Citizens, Politics, and Social Communication. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press. 1995.